Chemical and Thermal Characterization of an exopolysaccharide from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum BAL-29-ITTG

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.37636/recit.v8n4e405Keywords:

Exopolysaccharides, Monosaccharides determination, Nuclear magnetic resonance, Polysaccharides composition, Polysaccharides characterizationAbstract

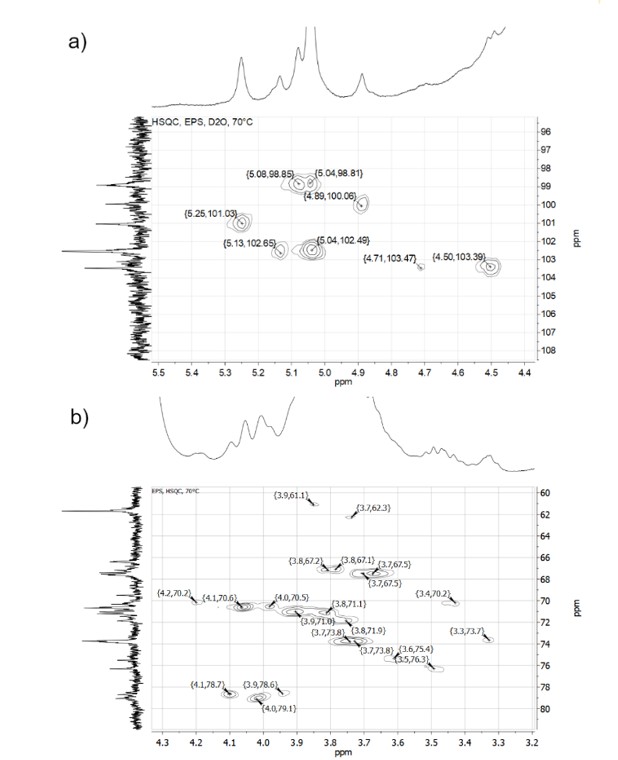

Exopolysaccarides (EPS) are biopolymers, which can be produced by lactic acid bacteria. In this work an EPS from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum BAL-29-ITTG was characterized by 1H, 13C, COSY, TOCSY and HSQC nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and viscometry. Thermal analysis and viscometry results suggested that ESP had a high molecular weight with a branched structure; to determine its main monosaccharides, the experimental chemical shifts of hydrogens and carbons obtained by NMR were loaded and compared with the database in the online software CASPER: http://www.casper.organ.su.se./casper/ Results showed that at least eight monosaccharides are present as components of this EPS, the most likely monosaccharides identified were: b-D-glucopyranose 1-4 and 1-6 linked: →4)-b-D-Glc-(1→; →6)-b-D-Glc-(1→ and a-D -manose 1-3, 1-4 and 1-6 linked: →3)-a-D-Man-(1→; →4)-a-D-Man-(1→; →6)-a-D-Man-(1→, although, data from FTIR and NMR also suggest N-acetylated residues.

Downloads

References

[1] S. L. Flitsch, “Enzymatic Carbohydrate Synthesis”, en Comprehensive Chirality, Elsevier, 2012, pp. 454-464. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-095167-6.00727-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095167-6.00727-8

[2] A. I. Netrusov, E. V. Liyaskina, I. V. Kurgaeva, A. U. Liyaskina, G. Yang, y V. V. Revin, “Exopolysaccharides Producing Bacteria: A Review”, Microorganisms, vol. 11, n.o 6, p. 1541, jun. 2023, doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11061541. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11061541

[3] S. A. M. Moghannem, M. M. S. Farag, A. M. Shehab, y M. S. Azab, “Exopolysaccharide production from Bacillus velezensis KY471306 using statistical experimental design”, Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, vol. 49, n.o 3, pp. 452-462, jul. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.05.012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2017.05.012

[4] S. R. Dave, K. H. Upadhyay, A. M. Vaishnav, y D. R. Tipre, “Exopolysaccharides from marine bacteria: production, recovery and applications”, Environmental Sustainability, vol. 3, n.o 2, pp. 139-154, jun. 2020, doi: 10.1007/s42398-020-00101-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42398-020-00101-5

[5] L. A. Silva, J. H. P. Lopes Neto, y H. R. Cardarelli, “Exopolysaccharides produced by Lactobacillus plantarum: technological properties, biological activity, and potential application in the food industry”, Ann Microbiol, vol. 69, n.o 4, pp. 321-328, abr. 2019, doi: 10.1007/s13213-019-01456-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-019-01456-9

[6] E. Korcz y L. Varga, “Exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria: Techno-functional application in the food industry”, Trends in Food Science & Technology, vol. 110, pp. 375-384, abr. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.014. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.014

[7] A. T. Adesulu-Dahunsi, A. I. Sanni, K. Jeyaram, J. O. Ojediran, A. O. Ogunsakin, y K. Banwo, “Extracellular polysaccharide from Weissella confusa OF126: Production, optimization, and characterization”, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 111, pp. 514-525, may 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.060. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.060

[8] Nguyen, Phu-Tho, T.-T. Nguyen, D.-C. Bui, P.-T. Hong, Q.-K. Hoang, y H.-T. Nguyen, “Exopolysaccharide production by lactic acid bacteria: the manipulation of environmental stresses for industrial applications”, AIMS Microbiology, vol. 6, n.o 4, pp. 451-469, 2020, doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2020027. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3934/microbiol.2020027

[9] A. K. Abdalla et al., “Exopolysaccharides as Antimicrobial Agents: Mechanism and Spectrum of Activity”, Front. Microbiol., vol. 12, p. 664395, may 2021, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.664395. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.664395

[10] T. Lin, C. Chen, B. Chen, J. Shaw, y Y. Chen, “Optimal economic productivity of exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria with production possibility curves”, Food Science & Nutrition, vol. 7, n.o 7, pp. 2336-2344, jul. 2019, doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1079. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1079

[11] Z. Liu et al., “Characterization and bioactivities of the exopolysaccharide from a probiotic strain of Lactobacillus plantarum WLPL04”, Journal of Dairy Science, vol. 100, n.o 9, pp. 6895-6905, sep. 2017, doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11944. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-11944

[12] R. D. Ayivi et al., “Lactic Acid Bacteria: Food Safety and Human Health Applications”, Dairy, vol. 1, n.o 3, pp. 202-232, oct. 2020, doi: 10.3390/dairy1030015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy1030015

[13] L. Yu et al., “Purification, characterization and probiotic proliferation effect of exopolysaccharides produced by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HDC-01 isolated from sauerkraut”, Front. Microbiol., vol. 14, p. 1210302, jun. 2023, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1210302. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1210302

[14] J. Wang et al., “Optimization of Exopolysaccharide Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum R301 and Its Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities”, Foods, vol. 12, n.o 13, p. 2481, jun. 2023, doi: 10.3390/foods12132481. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12132481

[15] J. Xiong, D. Liu, y Y. Huang, “Exopolysaccharides from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: isolation, purification, structure–function relationship, and application”, Eur Food Res Technol, vol. 249, n.o 6, pp. 1431-1448, jun. 2023, doi: 10.1007/s00217-023-04237-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-023-04237-6

[16] D. Meghwal, K. K. Meena, R. Singhal, L. Gupta, y N. L. Panwar, “Exopolysaccharides producing lactic acid bacteria from goat milk: Probiotic potential, challenges, and opportunities for the food industry”, ap, vol. 12, n.o 2, dic. 2023, doi: 10.54085/ap.2023.12.2.22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54085/ap.2023.12.2.22

[17] M. Ayyash et al., “Exopolysaccharide produced by the potential probiotic Lactococcus garvieae C47: Structural characteristics, rheological properties, bioactivities and impact on fermented camel milk”, Food Chemistry, vol. 333, p. 127418, dic. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127418. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127418

[18] Q. Xu, M.-M. Wang, X. Li, Y.-R. Ding, X.-Y. Wei, y T. Zhou, “Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and action mechanisms of exopolysaccharides from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Z-1”, Food Bioscience, vol. 62, p. 105247, dic. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.105247. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2024.105247

[19] T. Bouzaiene et al., “Exopolysaccharides from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum C7 Exhibited Antibacterial, Antioxidant, Anti-Enzymatic, and Prebiotic Activities”, Fermentation, vol. 10, n.o 7, p. 339, jun. 2024, doi: 10.3390/fermentation10070339. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation10070339

[20] M. Kowsalya et al., “Extraction and characterization of exopolysaccharides from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain PRK7 and PRK 11, and evaluation of their antioxidant, emulsion, and antibiofilm activities”, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 242, p. 124842, jul. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124842. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124842

[21] Y. Jiang y Z. Yang, “A functional and genetic overview of exopolysaccharides produced by Lactobacillus plantarum”, Journal of Functional Foods, vol. 47, pp. 229-240, ago. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.05.060. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2018.05.060

[22] J. I. Ramírez-Pérez et al., “Effect of linear and branched fructans on growth and probiotic characteristics of seven Lactobacillus spp. isolated from an autochthonous beverage from Chiapas, Mexico”, Arch Microbiol, vol. 204, n.o 7, p. 364, jul. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s00203-022-02984-w. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-022-02984-w

[23] L. M. C. Ventura Canseco, R. O. Suchiapa Díaz, M. C. Luján Hidalgo, y M. Abud Archila, “Producción y bioactividades de los exopolisacáridos de Lactiplantibacillus plantarum BAL-29-ITTG utilizando un diseño experimental Plackett-Burman”, Rev. Mesoamericana de Investigación, vol. 3, n.o 3, 2023, doi: 10.31644/RMI.V3N3.2023.A03. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31644/RMI.V3N3.2023.A03

[24] K. M. Dorst y G. Widmalm, “NMR chemical shift prediction and structural elucidation of linker-containing oligo- and polysaccharides using the computer program CASPER”, Carbohydrate Research, vol. 533, p. 108937, nov. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2023.108937. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2023.108937

[25] A. K. M. H. Kober et al., “Exopolysaccharides from camel milk-derived Limosilactobacillus reuteri C66: Structural characterization, bioactive and rheological properties for food applications”, Food Chemistry: X, vol. 25, p. 102164, ene. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102164. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102164

[26] A. A. Al-Nabulsi et al., “Characterization and bioactive properties of exopolysaccharides produced by Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus isolated from labaneh”, LWT, vol. 167, p. 113817, sep. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113817. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113817

[27] T. Hong, J.-Y. Yin, S.-P. Nie, y M.-Y. Xie, “Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: Progress, challenge and perspective”, Food Chemistry: X, vol. 12, p. 100168, dic. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2021.100168. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2021.100168

[28] M. Mathlouthi y J. L. Koenig, “Vibrational Spectra of Carbohydrates”, en Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry, vol. 44, Elsevier, 1987, pp. 7-89. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2318(08)60077-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2318(08)60077-3

[29] X. Wang, C. Shao, L. Liu, X. Guo, Y. Xu, y X. Lü, “Optimization, partial characterization and antioxidant activity of an exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus plantarum KX041”, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 103, pp. 1173-1184, oct. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.118. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.118

[30] O. Braissant et al., “Characteristics and turnover of exopolymeric substances in a hypersaline microbial mat: EPS turnover in a hypersaline microbial mat”, FEMS Microbiology Ecology, vol. 67, n.o 2, pp. 293-307, feb. 2009, doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00614.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00614.x

[31] S. A. Barker, E. J. Bourne, M. Stacey, y D. H. Whiffen, “Infra-red spectra of carbohydrates. Part I. Some derivatives of D-glucopyranose”, J. Chem. Soc., p. 171, 1954, doi: 10.1039/jr9540000171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/jr9540000171

[32] J. Wang, X. Zhao, Y. Yang, A. Zhao, y Z. Yang, “Characterization and bioactivities of an exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus plantarum YW32”, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 74, pp. 119-126, mar. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.12.006. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.12.006

[33] F. Zamora, M. C. González, M. T. Dueñas, A. Irastorza, S. Velasco, y I. Ibarburu, “Thermodegradation and thermal transitions of an exopolysaccharide produced by Pediococcus damnosus 2.6”, Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B, vol. 41, n.o 3, pp. 473-486, jun. 2002, doi: 10.1081/MB-120004348. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1081/MB-120004348

[34] V. B. Bomfim et al., “Partial characterization and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharides produced by Lactobacillus plantarum CNPC003”, LWT, vol. 127, p. 109349, jun. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109349. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109349

[35] H. E. Gottlieb, V. Kotlyar, y A. Nudelman, “NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Laboratory Solvents as Trace Impurities”, J. Org. Chem., vol. 62, n.o 21, pp. 7512-7515, oct. 1997, doi: 10.1021/jo971176v. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/jo971176v

[36] N. Čuljak et al., “Limosilactobacillus fermentum strains MC1 and D12: Functional properties and exopolysaccharides characterization”, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 273, p. 133215, jul. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133215. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133215

Published

Issue

Section

Categories

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Rony Obed Suchiapa Diaz, Lucia Maria Cristina Ventura Canseco, Alejandro Ramírez Jiménez

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The authors who publish in this journal accept the following conditions:

The authors retain the copyright and assign to the journal the right of the first publication, with the work registered with the Creative Commons Attribution license 4.0, which allows third parties to use what is published as long as they mention the authorship of the work and the first publication in this magazine.

Authors may make other independent and additional contractual agreements for the non-exclusive distribution of the version of the article published in this journal (eg, include it in an institutional repository or publish it in a book) as long as they clearly indicate that the work it was first published in this magazine.

Authors are allowed and encouraged to share their work online (for example: in institutional repositories or personal web pages) before and during the manuscript submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, greater and more quick citation of published work (see The Effect of Open Access).